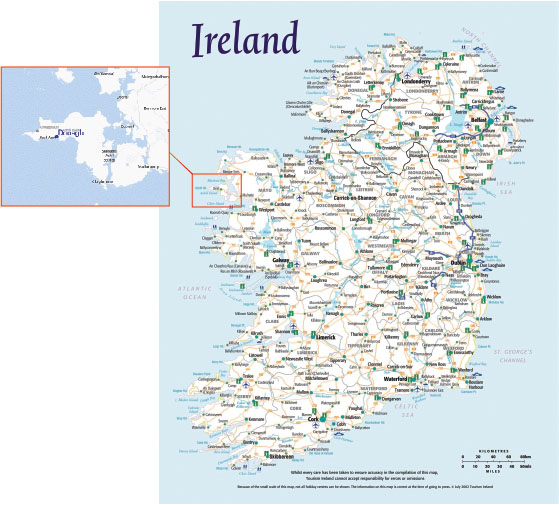

The Achill Archaeological Field School (AAFS) is developing a detailed understanding of the archaeology and history of Slievemore, the largest mountain on Achill Island which dominates the western half of Achill Island in Ireland.

Achill is the largest of the islands off the Irish coast and marks the most north westerly point of Ireland. The Achill Archaeological Field School (AAFS) was established in 1991 as a Training School for students of archaeology, anthropology and related disciplines. The field school is located in the village of Dooagh (pronounced Do-ah) towards the western end of Achill Island.

AAFS’ original research design was to develop a detailed understanding of the archaeology and history of Slievemore, the largest mountain on Achill Island which dominates the western half of Achill Island (see below). AAFS archaeologists and students, by combining surveys of standing monuments with selective excavation, have greatly increased the number of known sites on and around Slievemore and the excavations are providing important information about many of the individual sites. However, the survey work has shown that there is far more archaeology than could have ever been imagined at the outset and every year brings new surprises and discoveries. In addition to the work on Slievemore itself, several excavations have now been undertaken at other locations on the island, and quite a number of our students have returned to Achill in order to undertake their own post-graduate studies at sites they have first discovered during their time with the field school.

1991 to 2006

Between 1991 and 2006 the focus of the research was on the famous Deserted Village at Slievemore, a massive eighteenth and nineteenth century settlement strung out along the lower south-facing slopes of Slievemore Mountain (Fig. 3).

Fig 3-Part of the Deserted Village on Slievemore

Two of the houses in the centre of the settlement (Figs. 4 and 5) were excavated along with numerous surrounding features such as garden plots, a mysterious passage and underground chamber and a finely laid metaled-roadway.

As one of the very first occasions in Ireland that such relatively recent buildings had been the focus of a dedicated archaeological research project these excavations were of considerable importance during the development of Post Medieval Archaeology as an independent subject in Ireland, where archaeological interest had sorely lagged behind other parts of Western Europe and North America. The tremendous finds assemblage recovered from the excavations is perhaps unique in terms of its size and the level of detail and accuracy of its recording. The finds assemblage is so large that work on the ceramics, glass objects and metal items continues to this day. Through the analysis of material recovered from Slievemore and several other subsequent projects in neighbouring counties the understanding of the lives of the eighteenth and nineteenth century inhabitants of western Ireland has been subtlety but importantly altered.

2006 to 2010

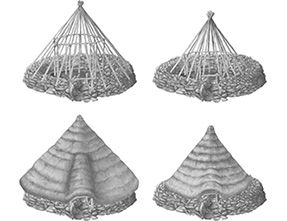

Towards the end of the 2006 three small test pits were excavated in one of the Bronze Age roundhouses that had been identified on the slopes overlooking the Deserted Village. These test pits led to a five year investigation of two of these buildings which turned out to be some of the best preserved Bronze Age buildings in the whole of Ireland. Work on the first of these houses was completed during 2008 and even larger scale investigations of the second example began in 2009 which took three years to complete (Figs. 6-10).

These two massive stone built structures were occupied in the Middle Bronze Age, sometime around 1300 BC. They are genuinely monumentally sized structures, with elaborate entrance passages and stone built walls over 2m thick and still standing today to a height of up to 1.7m. They appear to mark the final two buildings at the western end of a well-spaced east to west row of similar houses which may contain as many as ten additional buildings. The Bronze Age houses are set within a large and complex pre-bog field system and much of the 2010 and 2011 season was spent surveying these field walls and excavating numerous trenches over them to establish their nature. During the final stages of work on the second building it was conclusively demonstrated that three of these field walls were directly attached to the outer wall of the building. Pre-bog field walls have proven remarkably difficult to date directly and this clear association between the field walls and the residence is as important as it is rare.

2010

As work neared completion on the two Bronze Age roundhouses attention was turned to a nearby series of terraces where two small circular foundations could just be seen poking out of the bog. In 2010 the field school investigated the higher of these structures, revealing a circular building with a small internal area but surprisingly large walls. The building was approached via a well-laid flagstone path and a much slighter sub-rectangular building had been tagged onto its downslope side. The circular building overlay a large of field wall and outside the two buildings there were massive ash deposits. Unfortunately no dateable artefacts were recovered during the excavation and function and date of the site remained obscure.

2011

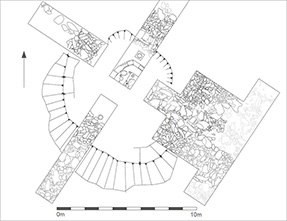

In 2011 the lower of the two circular buildings on the terraces was investigated. The building was very similar in form to the building investigated in 2010 (Fig. 11) but there was no obvious entrance and almost the entire interior was occupied by a stone built fire box filled with intensely burnt soil deposits. A narrow gap through the wall led right into the corner of the firebox. This gap was too narrow to be used as an entrance passage and was almost certainly a flue for controlling airflow into the fire box. Clearly this building represented an early kiln (Fig 12), but what was it for?

Soil samples failed to yield the expected quantities of charred grains that would be expected from a corn drying kiln. However several Early Medieval glass beads were recovered from the building, one of which from a context closely associated with the firebox. This suggests the possibility that it may have been a glass furnace, a type site as yet wholly unknown from such an early date in Ireland although such a function remains speculative at present. That Early Medieval glass beads were recovered from what had assumed to be a Bronze Age building was quite a surprise but this date was subsequently confirmed by a series of radio carbon dates. As with the first building a small sub rectangular building had been tagged onto the downslope side of this building.

2012

During the first part of 2012 excavation work shifted away from Slievemore to Keem Bay (Fig. 13) at the very western end of the island.

Here the ruins of a small stone built manor house sits at the back of the enclosed farmland, high up on the slopes overlooking the achingly pretty bay. The ruins were once the residence of Captain Boycott (Fig. 14), who subsequently moved to southern Mayo where he was subject to an organized process of ostracisation by Irish land reformers, a method of resistance that now bears his name.

The excavation revealed the original foundations for the earliest phase of this building, a galvanized steel shell supported by a timber frame and standing on a stone plinth. This building was probably occupied by Boycott when he arrived on the island in the 1850’s but remained in use even after he had twice extended the building in stone. The buildings ultimate destruction by fire is well attested by the remains of molten and twisted lumps of window glass. The finds from the excavation, consisting of several hundred artefacts, is providing a very interesting comparative assemblage to the material from the Deserted Village on Slievemore, in particular as a reflection of differences in class, status and national identity as expressed through material culture.

One of the ongoing mysteries of Achill archaeology is the location of the various Megalithic sites recorded by W.G. Wood Martin in the late nineteenth century. Wood Martin was a notable antiquarian resident in Sligo. Only around half of the sites on Achill that he described in his book ‘The Rude Stone Monuments of Ireland’ can be confidently identified and the rest have yet to be firmly tied down. During the latter part of the 2012 season excavations took place at one of the possible megalithic tomb sites on Slievemore. Although the most likely conclusion of this excavation was that the site represents an eighteenth or nineteenth century field clearance cairn it was still an interesting excavation and a negative result is valuable in terms of narrowing down the possible location of Wood Martin’s missing megaliths.

2013

The first part of the 2013 season was spent working on House 6 towards the very western end of the Deserted Village at Slievemore. The excavations at House 6 were very successful and revealed a relatively simple structure that was built late in the overall sequence of the village. The house was divided into a living room and an animal byre by a well-built cross drain, indicative of animals still being kept indoors at this late date. Curiously the floors were all of beaten earth except for a rather rough pavement that led from the doorway to the north-west corner of the house where there was a small area of very finely laid flagstones adjacent to the small open fire.

Continuing the architectural theme in 2013 the excavations moved to the other side of the island entirely, where the Field School investigated an area immediately outside the beautiful Tower House at Kildavnet, a small late Medieval Tower House (castle) (Fig. 15).

Here the excavations revealed the lower courses of the Bawn wall that would have enclosed the tower and formed the outer defences (Fig. 16).

Prior to this work the former presence of such a feature had been suspected but not directly observed. Its discovery and investigation adds a considerable new element to the site and the project was regarded as a major success. Interestingly enough this site also had a former resident of some notoriety; Grace O’ Malley, the sixteenth century Pirate Queen of Clew Bay!

2014

In 2014 we began an exciting new project investigating an enigmatic site on the slopes of Slievemore known as the ‘Cromlech Tumulus’ (Fig. 17). The site had been classified as a ‘megalithic structure’ and archaeologists had debated its typology for well over 100 years. Our excavations have shown that the site is multi-period, comprising a Middle Bronze Age roundhouse with late medieval and post-medieval hut sites on top. In 2014 we also excavated the first in a series of trenches over a related monument known as the ‘Danish Ditch’, a pre-bog linear feature that travels between the roundhouse and an adjacent Neolithic court tomb.

The season also saw one of our most unusual digs—the post-medieval pony graveyard on Dooagh beach. Two large grave cuts were excavated revealing two well-preserved equine skeletons (Fig. 18). Examination of the two pony skeletons suggested that both animals had a hard working life and had been fed a nutritionally poor diet. The horseshoes associated with the two excavated ponies indicated that the animals date from the middle of the 19th century or later. Local accounts indicate that animals were being buried in this location until the 1950s. The site seems to have been used for the burial of large animal carcasses in a community that was too far removed from an abattoir to make removal of animals feasible.

2015-2016

In the 2015 and 2016 seasons we returned to the ‘Cromlech Tumulus’ and ‘Danish Ditch’, excavating new trenches over both. 2015 was a particularly exciting year as we uncovered a carved beach pebble resembling a human face (Fig. 19) buried in a pit in the floor of the Bronze Age house. The carved object is very unusual and one of only a handful of examples of representative art from prehistoric Ireland. In 2016 we made another important discovery on Slievemore, this time at the ‘Danish Ditch’. Our slot trench over the feature indicates that it is probably a pathway flanked with two stone walls rather than simply a field wall.

In the second half of 2015 we moved to Keem Bay to the site of a pre-Famine settlement. In the early 19th century, the settlement consisted of a cluster of c.40 buildings on a shoulder of well-drained land overlooking the bay. Today little remains apart from the low grassed-over footprints of some of the houses. In 2009 a small test excavation had been carried out at the largest surviving footprint, Building 3. In 2015 we finished out the excavation of Building 3 (Fig. 20). The structure was revealed to be a small well-made dwelling defined by stone and earth walls, with a central hearth, a single southwest-facing doorway, and a stone-lined drain. A neighbouring structure, Building 4, was excavated in 2016, it was slightly smaller but was similarly constructed. The buildings yielded an assemblage of coarse earthenware and refined earthenwares, mostly made in England and Ireland.