October 8, 2010

by Katie Murtough

After four weeks in the trenches braving bipolar weather systems bent on eroding our findings or the top layers of our skin, carrying sand upon my body as a constant companion to my daily activities, preventing the local canids from making off with what they could only reasonably assume were the equivalents of the bones fed to them by their owners, uncovering a Drawsko vampire, and acquiring the mark of any dedicated archaeologist whose work requires their backside to commune with the unforgiving sun, I would not have traded any moment of my field school experience. Along with nineteen other students, I spent a portion of my summer at the Slavia field school in mortuary archaeology located in the small, rural community of Drawsko, Poland. The focus of the field school was in bioarchaeological excavation methods on a site located in the middle of an agricultural field, a field whose topsoil reminded many of us of the sand one would expect to find at a beach. The sandy substrate caused all of us to collapse a few walls here and there, but for the most part my first archeological field experience resulted in me discovering my passion and a few hidden talents, such as mapping, that I would have otherwise been unaware of.

The site itself bears an interesting history. The area became the final resting place for many people over several thousand years, first with the Bronze Age Lusatian culture, followed by the Jastorf culture of the Iron Age, and finally the 17th-18th century Christian Protestants. Why this particular region had such a draw to it that it became a designated burial ground on multiple occasions, no one truly knows. The location of the site, however, used to be referred to by the Polish word for ‘rolling hills,’ and it is believed by some that this now absent geological feature could have been a key factor in why the area held such a spiritual significance.

The Lusatian people cremated the deceased, placing their cremains in large urns and burying the clay pots with smaller secondary vessels that served as offerings to be used in the next life. In line with their culture’s history, we uncovered many Bronze Age pottery sherds and cremains. On one occasion a completely intact secondary vessel was recovered. It is hard to describe the emotion you experience when you hold something in your hands that you know was last touched by another human being over two-thousand years ago. In addition to being in awe over the small pot and wondering about the artist who had used their fingernails to carve the intricate design upon its surface, I couldn’t help but think: “don’t drop it, don’t drop it, don’t drop it…”

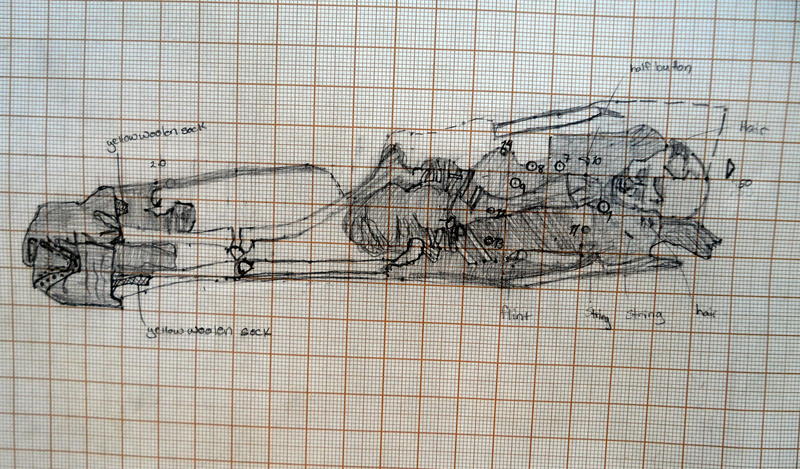

We collected and inventoried many pottery sherds and cremains, some of which were undoubtedly from the later Jastorf cremation pits, but most of our excavations centered on the careful removal of the 17th-18th century Christian inhumations. Because it was against God’s law to burn the deceased, individuals from this time period were buried in coffins, their bodies left to the natural processes of decay. While often a long and physically draining process, it was extremely rewarding to work on a feature through the initial observation of a coffin outline down to the complete display of the individual’s bones. You can imagine the fragility of these skeletons, especially since on several occasions our site was exposed to heavy rain, and so their careful removal often required a little bit of creativity and a whole lot of patience. But the pay-off was worth the effort and considering how delicate many of the skeletons were, I was very grateful for the staff allowing us almost complete control over the features we were excavating.

Perhaps the two most exciting discoveries made during our stay in Drawsko were the remains of an older woman thought to have been a vampire during life, and those of a man whose preservation was so great that we were able to recover nearly intact leather boots, woolen socks, buttons, and coffin lining. The vampire that was recovered is called as such due to the placement of certain grave goods in relation to her body. Early Christian settlers feared that people deemed unpleasant or evil in life would, upon death, return to suck the life force out of the living, hence the modern nickname, vampire. These individuals were typically found without having been given what was considered a formal burial during the 17th-18th centuries. They were often laid out in a pit with large stones placed on their throats, coins in their mouths and iron sickles stretched across their lower bodies so as to sever the vampire if they happened to raise themselves from their resting place. The team of archaeologists and osteologists who served as our mentors during the field school has only uncovered a handful of such individuals over the past couple of years, so the discovery of one this season was quite exciting.

Whether I was in lab deciphering an individual’s life story from the subtle language of their bones, in the field mapping the remains of a small child, or exploring Poland on the weekends, I had an experience that will stay with me for a life time. The field and lab staff was wonderful and their willingness to let us participate in nearly all aspects of an archaeological excavation with little instructor intervention was truly invaluable. The weekly lectures and quizzes allowed us to gain more background knowledge concerning the remains being recovered, and I left Drawsko having learned more in four weeks of field school than I ever could have in a quarter at my university. Looking back on my time spent in the field, I couldn’t imagine having missed this opportunity and so I am extremely grateful for having received the Jane C. Waldbaum scholarship to fund my travel.