Betsey Robinson, associate professor of History of Art and Architecture at Vanderbilt University, focuses her research on the Corinth Excavations at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Robinson shares with us why you should know about archaeologist Bert Hodge Hill, whose work at the Corinth Excavations, particularly the Peirene spring and fountain-house, is crucial to our understanding of the site.

What got you intrigued about Bert Hodge Hill?

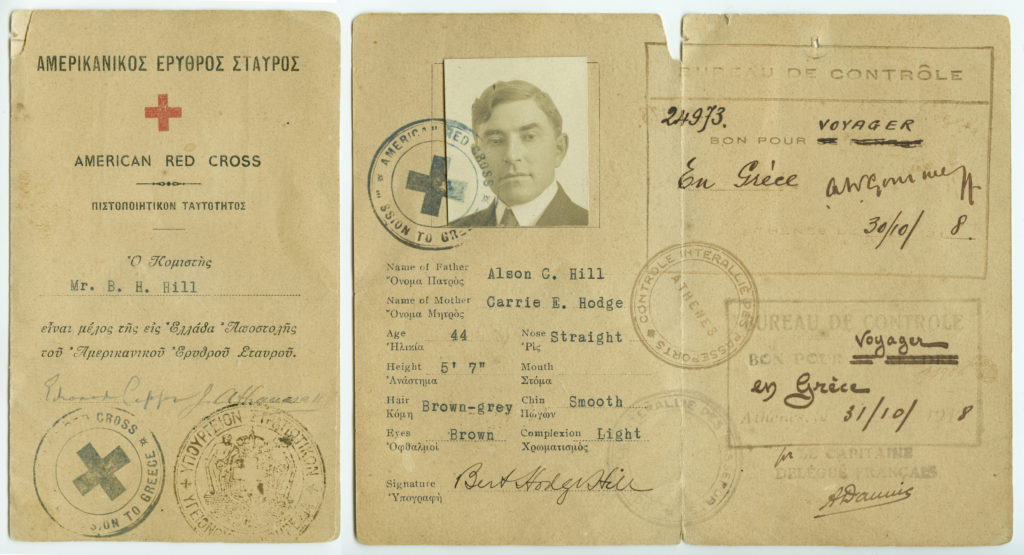

Staying in “Hill House,” the headquarters of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) Corinth Excavations, and working on the fountains and water supply of the ancient city, I became fascinated with Bert Hodge Hill’s life and work. Hill (UVM BA 1895; Columbia MA 1900) studied at the ASCSA from 1901 to 1903, first as a Columbia Drisler Fellow, then as a Fellow of the Archaeological Institute of America. He was hired by the ASCSA as Director in 1906, at just 32 years old, served in that role until 1926, and would continue to live and work in Greece for the rest of his life.

Part of the Director’s job was to lead the ASCSA’s Corinth Excavations, which had begun just a decade before, in 1896, and Hill also took on the responsibility to publish the three great fountains of Corinth: Peirene, Glauke and the so-called Sacred Spring. Hill’s fieldwork down to the 1940s is recorded in at least 33 unpublished notebooks and numerous “casual notes,” all archived at Corinth. They are an incredible resource for understanding Corinthian topography and monuments, and they reveal Hill’s development as an archaeologist and supporter of interdisciplinary work, his infinite curiosity, and his dedication to the site, to the village of Corinth, and to Greece. For me, reading through the notebooks on-site was like being taught by the master himself; he pointed out details that I might otherwise have missed, and he sharpened my architectural eye. Hill and his family left their private papers to the ASCSA, and those offer a unique view of Hill as a person as well as a professional.

Hill oversaw work across Ancient Corinth, but he devoted the greatest time and effort to the Peirene spring and fountain-house. Peirene’s discovery in 1898 was the Americans’ first great success at Corinth. Mentioned by Pindar, Euripides, Callimachus and other ancient authors, the famous monument gave them something to brag about. And thanks to Pausanias, who visited Corinth in the mid-2nd century CE and described the monument in his guide to the site, Peirene’s discovery told the excavators where to find Corinth’s Forum.

By the time Hill became Director, however, Peirene was proving to be more of a curse than a blessing. The water flowed continuously from water collection tunnels extending about 1 km underground, and was captured in a series of ancient basins behind a grand façade. At times, Hill managed get the system to work almost like new, but storms led to floods, and the nature of the aquifer made it almost impossible to keep Peirene clean and healthy. This was a problem because it still was the main source of drinking water in Ancient Corinth! Hill would labor to tame Peirene through his Directorship and beyond.

Please share one anecdote that you see as representative of Hill and his work.

Hill was nothing if not devoted to his work, persevering through bouts of typhoid (caught from Peirene water), malaria, and other challenges. In the summer of 1931, he wrote to a colleague:

The forenoon of July 30, as I was going down for the second period of the day’s work in Peirene, I fell and rolled down a bank, receiving a number of bad knocks in the back and left hip, breaking my right forearm and more or less dislocating the wrist. Two of the blows in the back were close to the spine and so severe that I at first feared I was quite done for. It was only when I found I could walk (and so could not have really injured the spinal cord) and had made my painful way back to the house that I noticed that the arm was broken. With my back in the condition it was I could not face a journey to Athens. So I had an experienced, though unlicensed, bonesetter of New Corinth come and put the radius and ulna back where they belonged (or nearly enough there for practical purposes—the wrist does not quite match the sound left one), and first consulted a regular surgeon in Athens on August 11. On August 24 he removed the bandages. . . .

Before long, he was back in the dank tunnels of Peirene, dodging bats, climbing over dams, and wading through the water inside, taking notes with his left hand.

What do you see as Hill’s chief achievements?

Hill suffered from terrible writer’s block, so while he produced annual reports and a few articles, his two monographs—both very valuable—appeared only after his death. He was nonetheless highly influential in the field of classical archaeology, largely through teaching topography and architectural autopsy to the student members of the ASCSA, and training them in excavation and archaeological documentation at Corinth.

Already as a student as far back as 1902, Hill saw the potential of stratigraphy in archaeology, and as Director, he worked to refine stratigraphic analysis with his students. Drawn sections help us to make sense of their excavations, and some have even supported new interpretations and dating schemes. Moreover, archaeologists trained by Hill, for example Carl Blegen, would further advance this “science of archaeology” in their own excavations in the Corinthia and beyond.

Hill’s humanitarian efforts also stand out. At Corinth, he worked tirelessly with the American Red Cross, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Greek health organizations for decades, to bring Peirene up to modern standards for drinking water. During World War I, he liaised with the US Army and took part in anti-typhus campaigns in Macedonia and Bulgaria. Later he served on committees to support and resettle Greek refugees from Turkey in the 1920s. As World War II heated up, he secured all the contents of the archaeological museum at Ancient Corinth under sandbags, then chaired the repatriation committee that sent Americans safely home. He stayed on at Corinth, excavating when he could, until the US entered into the war.

Finally, explain in 50 words (or so) why Bert Hodge Hill is an archaeologist the public should know more about.

Bert Hodge Hill was an inspiring teacher, an innovative archaeologist, a philhellene, and a humanitarian. Although he wasn’t a prolific author, he was a prominent and influential classical archaeologist in the first half of the 20th century, and he trained generations of leaders in the field. I’ve barely scratched the surface here. Check out the sources below for much more about Bert Hodge Hill’s work and the fascinating life he led!

To learn more about Bert Hodge Hill and his work, explore the following resources:

Notifications