Elizabeth Bartman is an independent scholar who specializes in Roman sculpture and its modern reception. She has long been active in the AIA, serving as a local Society leader, as a lecturer, Governing Board member, then First Vice President and finally, President (2011-2014). She never met Miss Richter but was delighted to learn that her favorite alcove in the main reading room of the American Academy in Rome was also Richter’s–it was where the books on ancient sculpture were shelved! We spoke to Bartman to learn more about Gisela Richter, and why she is an archaeologist you should know.

What intrigued you about Gisela Richter?

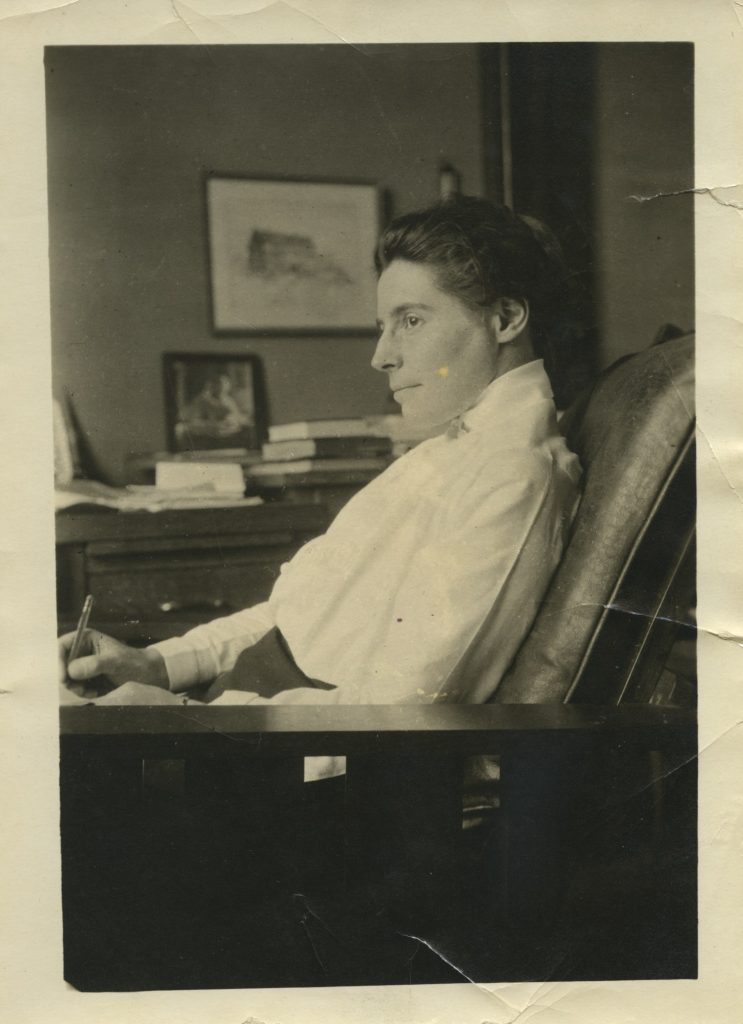

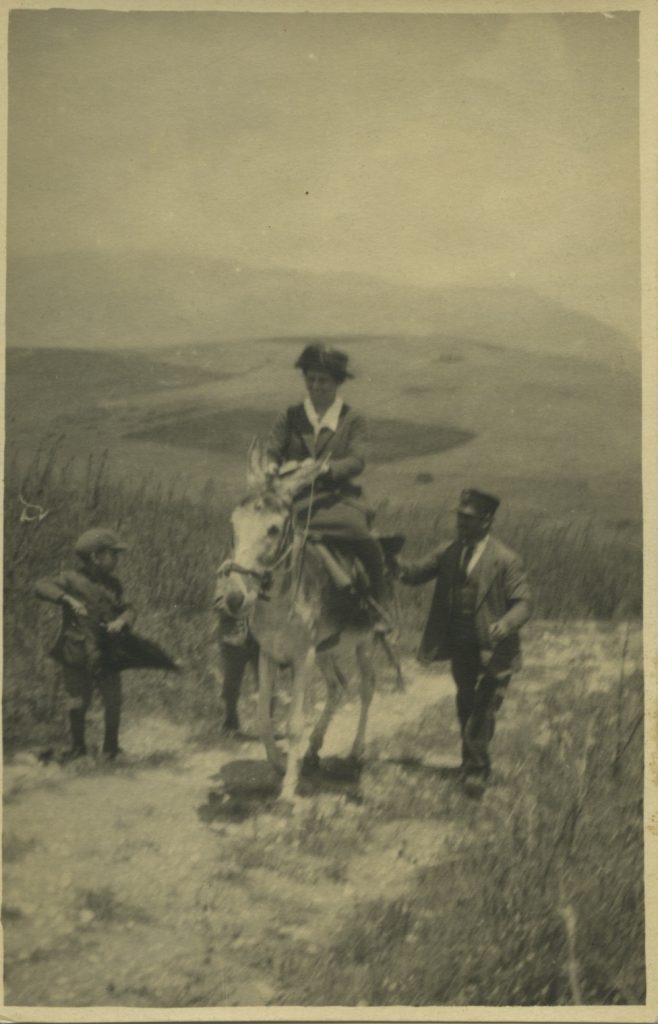

Gisela Richter died in her 90th year on Christmas Eve in 1972, a half century ago but still within living memory of people now in their 80s and 90s. Their personal reminiscences give an unmatched immediacy and authenticity to the story of an American archaeologist who had a huge impact on archaeology in the twentieth century, despite not herself engaging in fieldwork. My interest in Richter stems from our shared love of Rome, where she spent the last 20 years of her life; of the American Academy there, where she was a constant presence in the library from 1952 to her death; and of the Greek and Roman collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which were transformed by her curatorial activities during the many decades she worked there (1905-1948).

Please share one anecdote about Richter that you find interesting.

By all accounts, Richter was lively and vivacious, with an international circle of friends and colleagues. Professor Richard Brilliant, who as a student in Rome in the 1960s was invited to her Saturday lunches (other guests included Lily Ross Taylor) describes her as a “sparkler;” when he asked why she had never married, she told him that a husband would have had “other things” on his mind at bedtime, but she was too busy thinking about Greek art. This anecdote underscores not only her sense of humor but also her single-minded approach to her work. On a more serious level, it hints at her desire for autonomy: during her youth in the early twentieth century, marriage imposed many restrictive social conventions on middle-class women like Richter, while unreliable contraception made children nearly inevitable. For women of that era, “having it all” was impossible.

What are Richter’s chief achievements?

Her single-mindedness is on full display in her extraordinary publication record. From her start at the Metropolitan in 1905 as a research assistant studying Greek painted pots, over the next six decades she published book-length catalogues of much of the Museum’s classical collection (engraved gems, bronzes, Attic pots, Greek sculptures, Roman portraits, paintings) as well as the first introductory handbooks (1945, 1953). In addition, there were countless articles in the Met’s then-monthly bulletins on individual pieces to announce their arrival. Greek sculpture, her special love, featured in numerous books, both general works as well as specialized studies on particular genres such as gravestone or kouroi. She approached these latter topics with a standard formula: classification, evolution, and dating. What was said in a review of The Archaic Gravestones of Attica, published in 1961, could easily apply to many of her works: “scrupulously documented, amply illustrated, a model of catalogue raisonné, and something more: the testament of a lifetime’s devotion.” Almost all of her non-Met-related books were published by Phaidon Press, a fine arts publisher renowned for its high standards; beautifully produced, they featured elegant, Roman-inspired typefaces and hundreds of photographs. Many images were specifically commissioned from the superb, Athens-based photographer Alison Frantz; with their clear, straightforward prose and “objective” photography that eschewed dramatic effects, Richter’s volumes defined the study of Greek art for Anglophone readers during much of the twentieth century. Her Handbook of Greek Art, first published in 1959, went on to appear in nine editions.

Richter also promoted Greek art as a curator at the Metropolitan. By 1928 she was head of the Greek and Roman Department–the first woman to hold such a position in any of the Museum’s departments– and responsible for acquisitions. As Steve Dyson has documented, the pre-WWII years between 1900 and 1939 (when WWII all but curtailed acquisitions from abroad) saw the Met’s acquisition of over 200 works; the 1930s were an especially fertile period for acquiring Greek sculpture. Towards the end of her life, Richter singled out her most important additions to the collection: the Wounded Amazon once belonging to the Earl of Shelburne (Lansdowne House, London); the grave stele of Megakles topped by a sphinx; the relief of a lion attacking a bull; a gold sword sheath from South Russia; a stand signed by Kleitias; the head of the Roman emperor Caracalla. In that same memoir, she mentioned the question of forgery, always an issue with archaeological works like these that lack provenance; in the early twentieth century, many of the scientific techniques used today to determine authenticity (i.e. x-rays, thermoluminescence, spectrography, etc.) were not commonplace. There are fakes in many collections and no single curator can be expected to have the expertise to ferret them all out. Richter was deceived by the three colossal Etruscan terracotta warriors that had been bought by John Marshall for the Met in the early part of the century; by the time they were definitively revealed as fakes in 1961, Richter had retired from the Museum. To her credit, she did not dwell on the mistake.

Why should the public know more about Richter?

Born to an intellectual family of art historians, Richter was a scholar of the “old-school,” steeped in the ancient languages and practicing a largely formalist art history. During her years at the Met she witnessed the museum’s transformation from a casual assemblage of donated art works of varying quality to an encyclopedic collection of “masterpieces” overseen by trained curators and other professionals. As an astute connoisseur she would have applauded the Museum’s new direction, and as an indefatigable champion of Greek art through her prolific writing, Richter ensured the prominence of classical antiquity at the Met for many decades. But her appreciation went beyond the visual and intellectual–she also reveled in the technical aspects of ancient art and enthusiastically promoted “experiential archaeology” as a means of understanding ancient objects. She made ceramic pots, commissioned wooden furniture in the ancient mode, blew glass, learned bronze casting. For many years the Met had a Room of Technical Exhibits that showcased these creative processes.

To learn more about Gisela Richter and her work, please explore the following resources: