Explore the serenity of the highlanders on the route between Knossos and Ideon Cave on Minoan Crete.

The ancient Minoans are best known as seafarers, but excavations at the site of Zominthos, nestled in a plateau on Mt. Ida, Crete’s highest mountain, have shown that they were also highlanders. This important second-millennium B.C. site, located about 1,200 meters (nearly 4,000 feet) above sea level, lies on the ancient route between the palace at Knossos, the Minoans’ primary administrative center, and the sacred Ideon Cave, where many believe the legendary god Zeus was born and raised. Zominthos is the only mountaintop Minoan settlement ever to have been excavated and is yielding groundbreaking information.

A Special Message on the Passing of Professor Yannis Sakellarakis

All photos courtesy of the Zominthos Project unless otherwise noted.

The archaeological site of Zominthos is located in the mountains of central Crete, the largest of the Greek islands and the fifth-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Crete’s geographic position in the southernmost part of the eastern Mediterranean and its natural environment played a definitive role in the birth, development, and character of the Minoans (ca. 3100–1050 B.C.), the first European civilization.

Mountains have been the Cretan people’s most precious resource since ancient times. High ones, such as Ida, are exposed to low temperatures and snowfall in the winter, while their peaks and some plateaus are covered in snow for most of the year. Mountains can be natural shelters for those who know how to exploit their resources such as water, the most important one for farming activities. It is therefore quite reasonable to assume that the wider region of Zominthos was occupied from at least the Minoan period to modern times. Two nearby cheese dairies, both of which have been restored, date back at least to the 18th and the 19th centuries. At the older one, Mycenaean artifacts have come to light.

Over time, important geological factors—geomorphology, tectonic movements, the eruption of the nearby volcanic island of Thera, and the rise of the sea level—altered the natural environment of Crete to such an extent that the island’s historic course was affected. Additional factors, such as intensive agricultural cultivation, deforestation, and other human activities, resulted in a gradual change in the natural environment. Minoan settlements and cemeteries, artifacts, and ecofacts reveal the evolution of a society that was not only influenced by foreign factors, but also managed its resources so well that it developed into a great civilization.

The purpose of the multidisciplinary Zominthos Project is not only to uncover and study the site’s archaeological remains, but also to systematically investigate the relationship between the ancient people and their environment.

Professor Yannis Sakellarakis discovered the site in 1982, during his first day of excavations at the nearby Ideon Cave, when a shepherd told him about his pastures and sheep in an area called “Zominthos.” Intrigued by the pre-Hellenic place-name, he began small-scale excavations the following year, which revealed the Central Building that is now believed to have dominated one of the main Minoan routes up to Mount Ida, today called Psiloritis. Zominthos may have been used as a rest stop for visitors making their way from Knossos to the Ideon Cave, the great sanctuary cave near the peak of Ida, as is mentioned in Plato’s Laws (book I, 625B): “I dare say that you will not be unwilling to give an account of your government and laws; on our way we can pass the time pleasantly in and about them, for I am told that the distance from Knossos to the cave and the temple of Zeus is considerable; and doubtless there are shady places under the lofty trees, which will protect us from this scorching sun.”

Entrance to the Ideon Cave

Zominthos seems to have been occupied beginning the 17th century B.C., with an extensive settlement and a monumental Central Building that covers an area of 1,600 square meters (17,000 square feet). Beneath the Central Building, which was gradually developed from the 17th century onward, the remains of several earlier structures have been identified. Because of the severe climate conditions on the mountaintop—including snow during the winter months—the site may not have been used throughout the entire year, but rather as a seasonal habitat. During the summer months, people likely moved their flocks of sheep here, to higher altitudes, while exploiting natural resources, such as minerals, herbs, and pharmaceutical plants. These products, along with woolen textiles and olives, were the goods most commonly exported from Minoan Crete to Egypt and the Middle East.

Zominthos in the winter, covered in snow

The Central Building is extremely well preserved and some of its walls still stand at a height of 2.2 meters (7.2 feet). However, creating the foundation of such a huge building at this altitude is quite a complicated issue. Its unlikely location and size, as well as its careful construction, indicate the existence of a central authority that intended to control the region’s resources, including its flocks and pastures. Zominthos may therefore be considered a well-organized administrative complex—built on a strategic spot for the control of the area—that fully adapted to the inhospitable Cretan mountains. Its location on the ancient route to Psiloritis and the wealth of pottery found at the site indicate that it was likely also a religious and crafts center.

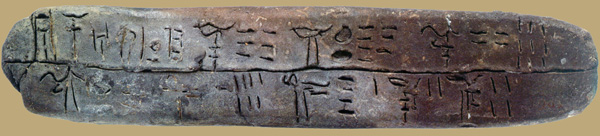

The accounting archives in the Linear B script from the palace at Knossos—about 40 kilometers (25 miles) from Zominthos—record thousands of sheep along with shepherds’ names. However, the location of the land where these sheep were grazing has always been a mystery. Zominthos and the neighboring regions have very prosperous pastures, so it could be that the sheep recorded in the Knossos tablets were mainly concentrated here at Zominthos. The Central Building’s importance is confirmed by its asymmetrical facades and orientation to the cardinal points, which are well-known characteristics of Minoan palaces. Zominthos was destroyed by an earthquake around 1600 B.C., which resulted in a fire that devastated the vast majority of building’s structure. But various finds from the Central Building indicate that the site continued to be used in Mycenaean, Archaic, Hellenistic, and Roman times.

Linear B tablet

After a gap of 17 years, archaeological work at the site of Zominthos resumed in the summer of 2005. Although only the ground floor is visible today, archaeological evidence suggests that the Central Building had at least two floors built of large blocks of local stone, some coated with white plaster and decorated with frescoes. Only 10 of at least 45 rooms of the ground floor have been partly or fully explored up to now, and the results can be summarized as follows: The rooms contained pottery, masses of animal bones, numerous fragments of carbonized wood, and several small artifacts. The vast majority of the pottery includes conical cups, cooking pots, and pithoi. Also, several ceramic water conduits have been found, probably indicating a central drainage system. In the western part of the Central Building, a complex consisting of at least two workshops was discovered.

Ceramics found in the Central Building

1. A 15-square-meter (161-square-foot) Ceramics Workshop (room 13) with more than 250 vessels for everyday use, some bronze and stone tools (including a knife, blade, and tongs), a cistern in the middle of the room (for the purification of the clay), and a potter’s wheel, near what was most likely the potter’s workbench. Ceramics had been placed on two benches running along the northern and southern walls, some of which were found in situ. Many of them were probably standing on wooden shelves on the walls, something that is indicated by numerous fragments of carbonized wood.

2. A workshop that might have been used for processing quartz crystal (among other items), a rare and valuable material, which in antiquity was believed to have magical properties. From this room three rhyta came to light, which along with the quartz crystals and the site’s other unique features, such as its location on the route that lead to the Ideon Cave, reinforce Central Building’s double use, as a place of worship and a crafts center.

Quartz crystals in situ

The Central Building was not an isolated structure but the dominant edifice of a settlement extending to an area of at least one acre, as indicated by the scattered pottery and the remains of walls. The excavation continues today, in order to reveal the structure of the whole building and identify the function of the rooms, as well as to preserve the natural environment and provide an opportunity to rebuild, as much as possible, the tranquillity of the Minoan period. Specifically, our team has made extensive efforts to reforest the site and the wider area. The most characteristic feature of the site is the tree Crataegus monogyna (the common hawthorn), which stands at a height of 12 meters (39 feet), and is the tallest-known example of its species. It has been named a “Listed Natural Monument” in Greece.

We wholeheartedly thank our donors that support the Zominthos Project. Their financial aid enables the continuous multidisciplinary research needed to build on our current knowledge of Minoan archaeology and the archaeology of the Cretan mountains.

Psychas Foundation

INSTAP

![]()

Paul & Alexandra Canellopoulos Foundation

Archaeological Society at Athens

National Bank of Greece

Cooperative Bank of Chania

Melissideo Foundation

Psychas Foundation

INSTAP (Institute for Aegean Prehistory—Study Center for East Crete)

![]()

Anonymous Greek donors

Notifications