Affiliation: University of California, Merced

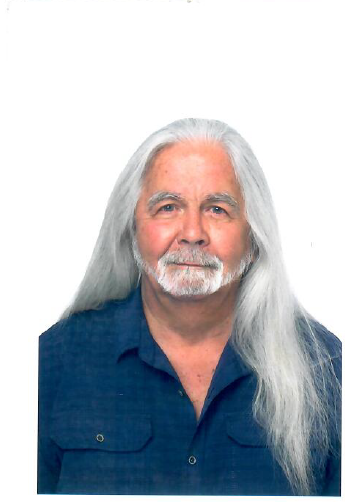

Professor Mark Aldenderfer is Distinguished Professor Emeritus and holds the Edward A. Dickson Emeriti Professorship Endowed Chair in the Department of Anthropology and Heritage Studies at the University of California, Merced; he is also Adjunct Professor with the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, Tucson His research focuses the comparative analysis of high altitude cultural and biological adaptations from an archaeological perspective, and he is likely to be the only archaeologist who has done research on the three high elevation plateaus of the planet—Ethiopian, Andean, and Tibetan—over the course of his career. He currently works in the High Himalayas of Nepal studying population movements and the archaeology of religion in pre-Buddhist and Buddhist eras. He holds his degrees from Wake Forest University (BA) and the Pennsylvania State University (MA and PhD). He has conducted fieldwork in Tibet, Nepal, Peru, Argentina, Belize, Guatemala, and Ethiopia, as well as many regions of the United States. Professor Aldenderfer was an AIA Norton Lecturer in 2013/2014.

In the mid-7th C, the Tibetan Empire was ruled by kings who controlled much of the plateau and the surrounding regions of the Central Himalayas. Through conquest and tribute, they became wealthy and powerful, and in death, they are said to have taken much of that wealth with them. Unlike their ancestors who were taken at death to heaven on a rope to join their predecessors, these rulers were interred in massive tombs in the Yarlung valley of central Tibet that housed not only themselves, but their attendants and even state ministers who accompanied them into the afterlife. In this lecture, I describe the rise of the empire, the death rituals of these kings, their tombs, and the wider context of mortuary practice on the plateau and the Himalayas.

· Although historians and Tibetologists since the early 20th C have collected and interpreted religious documents describing in general terms rituals of death and safe passage to the afterlife among the early peoples of the Himalayas, the archaeological record offered little insight into them. But recent research by archaeologists across the region have made extraordinary discoveries that both challenge and corroborate current understandings as well as identifying previously unknown traditions for both commoners and kings.

Our ancestors—and ourselves— have always lived within the shadow of mountains. The story of our enduring relationship with the mountains and plateaus of the world begins more than one million years ago at the margins of the Rift Valley in Ethiopia. There, at sites at elevations ranging from 2000-2400 m, our hominin ancestors obtained obsidian from outcrops and most likely foraged for food. Over the next million years, as our ancestors moved out of Africa into new habitats, they found both challenges and refuges in the mountain ranges they encountered. It has long been believed that the peopling of these high places came late in our evolutionary past—certainly within the past 40,000 years, but recently discovered evidence from Tibet challenges this assumption. In this presentation, I examine the biological, genetic, and archaeological evidence from around the world that provides a context for understanding how some of us became highlanders from our lowland origins, and when our species, or perhaps our ancestors, moved into these high places to live permanently.

Notifications